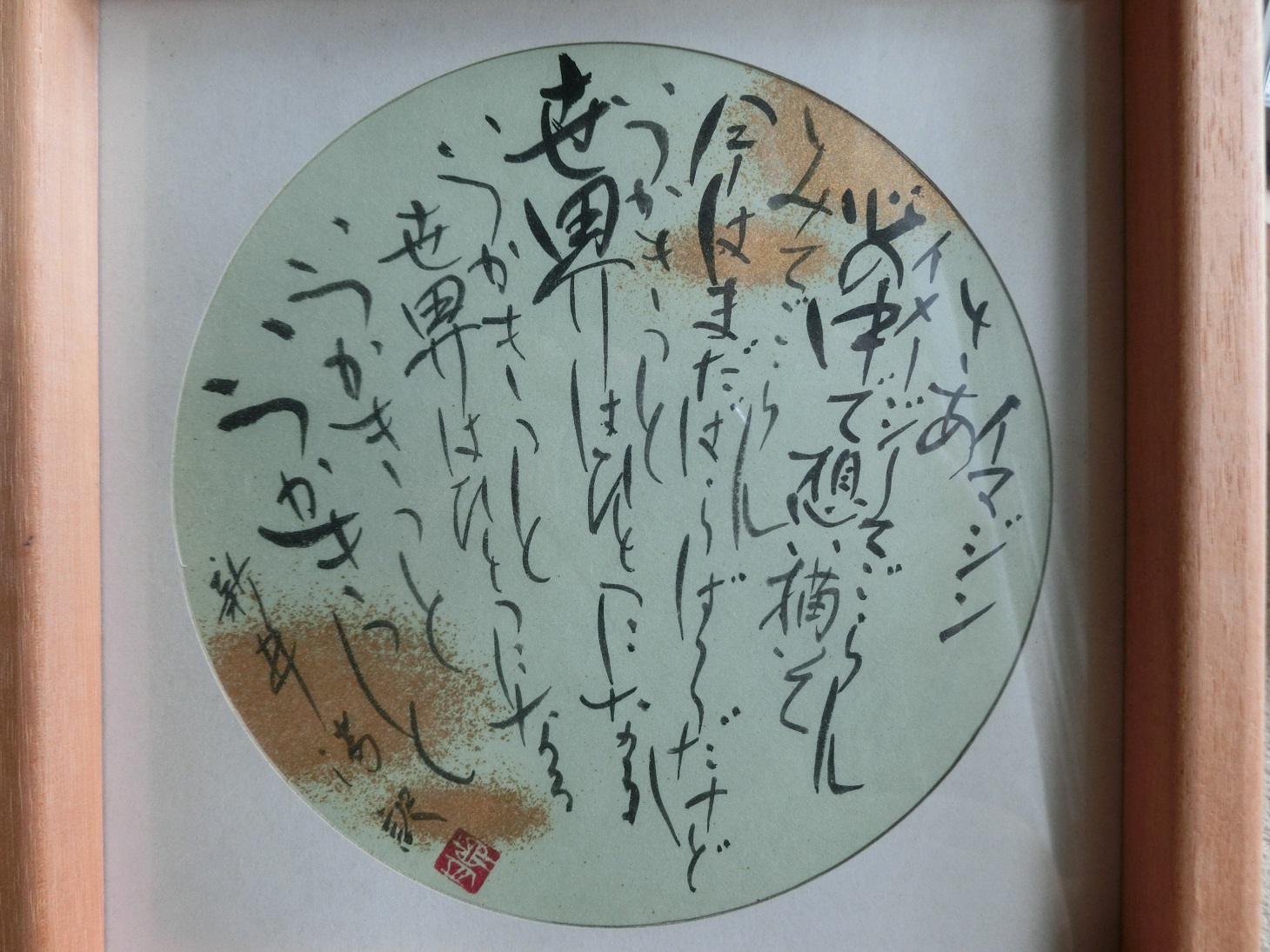

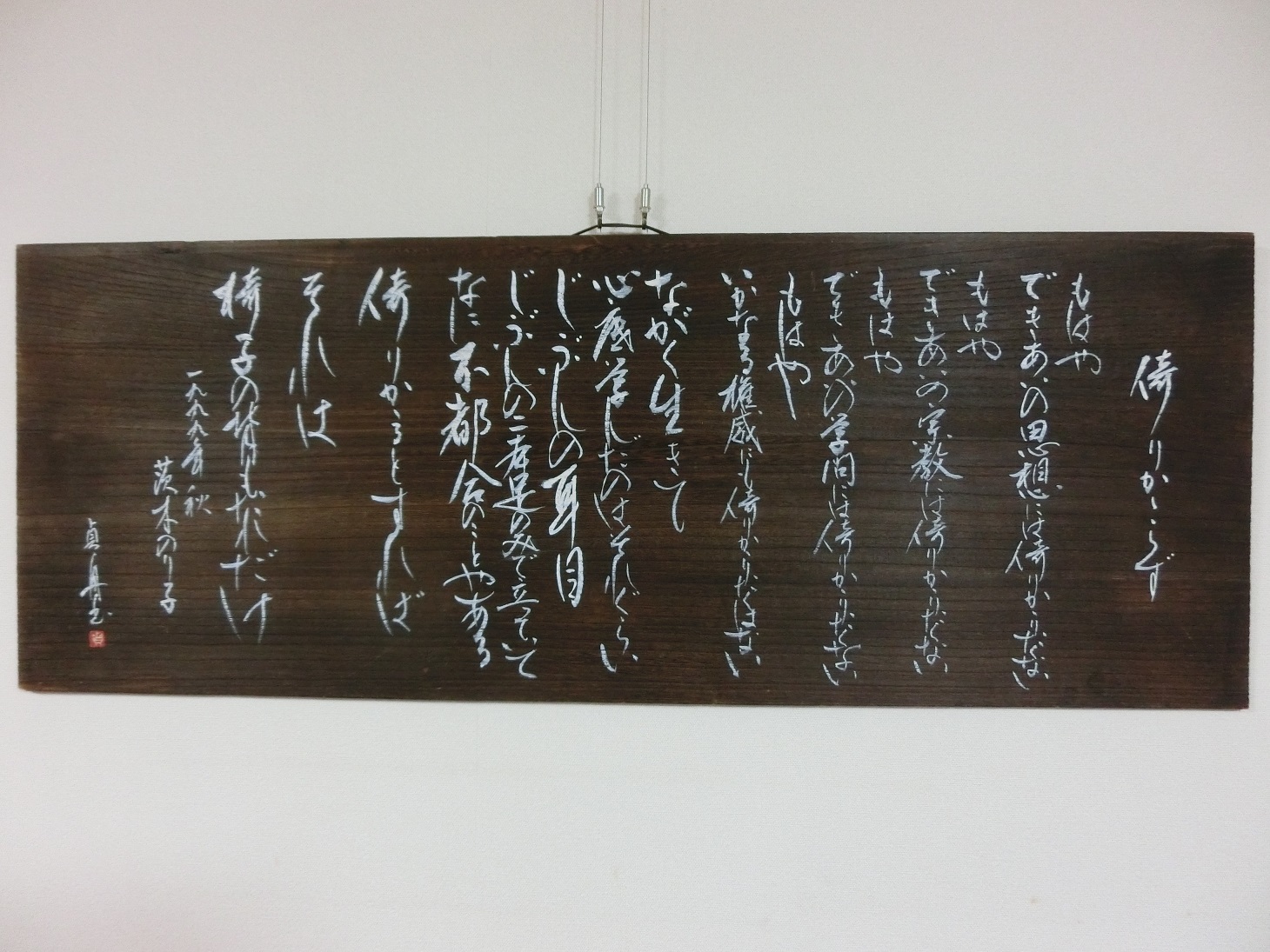

The writer's mother's work: A translation of of "Imagine"

It’s been a year and a half since my mother passed away—so suddenly. I’ll get to what I mean by “suddenly” later, but first, allow me to share two episodes that always come to mind when I think of her.

It was the autumn of forty years ago. I was a senior in university, and my father, turning sixty, told my mother that his company's upper management had approached him with an offer. If he accepted a solo transfer to the Tokyo head office, he could be promoted to executive director and have his retirement extended by three years.

My mother was washing my grandmother’s underwear when she stopped in her tracks, glared at my father, and launched into a verbal assault.

“A solo transfer? What are you gonna do about your meals? You’ve never cooked a thing in your life!”

“You’re just gonna leave your own bedridden mother behind?!”

“Executive director? What a non-sense! Ridilous!”

The tech-head engineer who specialized in ductile cast iron turned down the promotion offer and retired a few months later as the beloved “Head of Foundry Research.” I have another episode related to my mother’s belief that “Executive Director = Ridiculous.”

Let’s go back more than a decade earlier. I was in the second grade in elementary school. Through the paper sliding door, I sensed an intense atmosphere. My father had been hospitalized for depression. Today, we would call the cause “abuse of authority” in the workplace, and his company’s executive director and HR manager visited our home to press him to resign voluntarily.

One day before the hospitalization, my father tried to hang himself with his favorite necktie. My mother rushed over, grabbed a pair of dressmaking scissors, and cut the tie off. The snip sound of the scissors and her furious yell:

“What do you think you’re doing?!”

Meanwhile, my paternal grandfather—who couldn’t bear to accommodate a son with “that kind of illness”—had already summoned my uncle’s family to replace us, effectively cutting us off. And just then, the very people who had driven my father to mental disorder showed up.

“My husband wrote down everything that happened before and after he felt ill. Anyone who reads it can tell exactly what the cause was. If that’s the stance you're taking, we’ll take this to court. Don’t think we’ll just cry and sleep!”

The “ridiculous” executives left with their tails between their legs.

After that, my mother remained busy. She visited my father in the hospital every day with me in tow, always telling him he would get better. And he did—he was discharged in less than six months, returned to work, and as I mentioned earlier, continued until retirement.

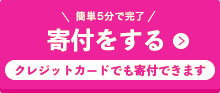

While teaching tea ceremony, flower arranging, and calligraphy, my mother also took care of and eventually saw off her in-laws' parents—yes, the same ones who once tried to throw us out. She then enjoyed some peaceful years with my fragile father, whom she had fiercely protected. A year before my father passed away, she moved to a place near me.

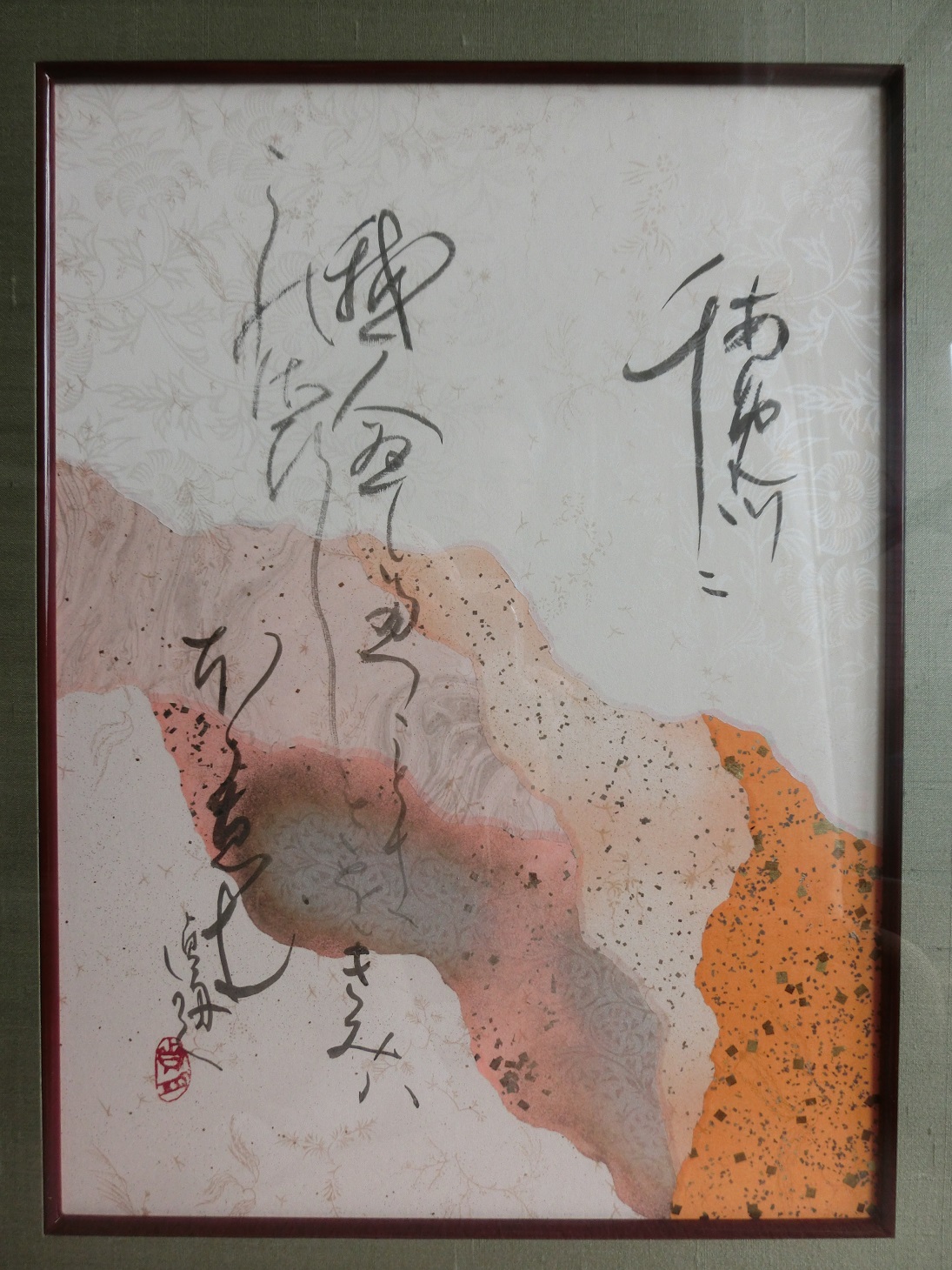

The writer's mother's work: A poem by Yaichi Aizu

My older brother doesn’t know either of these two stories. He had already moved out by the time of the first one, and my mother never told him about the second. She never let him visit our father in the hospital either. “Because he had university entrance exams soon,” she said.

But at the very least, if she had told him the second episode and shown him even a glimpse of what it was like to be a woman living in a conventional patriarchal family, the tragedy that happened over fifty years later might have been avoided.

After selling the old house, my mother moved into a brand-new apartment and began living alone. Later, I had to start making weekly business trips between Nagoya and Osaka, but I supported her by cooking and delivering homemade dishes—especially since she still had the passion to teach, even at the age of seventy over.

That life continued for nearly twenty years. Then she began to forget how to use the washing machine, forgot to eat the food I left for her, and claimed her money had been stolen. She moved into a nearby nursing home. Because she couldn’t control her appetite anymore, I stopped bringing sweets and instead brought art catalogues on my weekly visits. Eventually, she began to remember which exhibitions we had seen and when. I was overjoyed.

That day too, we looked at a catalogue and for some reason sang the old song “Wakamono-tachi” together.

“See you next time,” she said, waving her hand.

Every evening, I would turn on the remote camera and call her after watching her return to her room from the dining hall. That day, I saw my mother on camera—writhing in agony, unable to vomit on her own, supported by several staff members as she leaned over a sink.

What happened?! Mom!—All I could do was scream in front of the screen.

Soon, a call came from the staff. It turned out that my brother—who hadn’t visited even once in the three and a half years since she’d entered the nursing home—had given her far too many sweets. I hadn’t even known he planned to visit. Why hadn’t I warned him that food was strictly prohibited? I will never forgive myself.

My observations of my mother’s life are what led me to study gender. I wanted to share even one more day of her final chapter with her. I believed I could. With the staffs’ help, I had been as careful as possible.

That precious time was suddenly stolen from me—by a man who had been pampered as the “precious lineal grandson” by our great-grandmother, grandparents, and even our parents, and who, in the end, grew into a “ridiculous” adult with no consideration for his own old mother.

I can’t feel at ease on Wednesday evenings—ever since I saw her like that on the camera.

If a man grows up in a traditional and conventional extended family and lives in the Japanese patriarchal social system without learning anything from it, this is what happens.

We must not cut things off with just saying “Ridiculous!”.

The writer's mother's work: A poem by Noriko Ibaragi

![[広告]広告募集中](https://wan.or.jp/assets/front/img/side_ads-call.png)