The 9th session of the 2nd WAN Feminism Introductory Course was held on Thursday, April 18, 2024.

The topic of this session was “Globalization". Here we would introduce a report written by alary, a student of the course, which we hope could show you some tips of how the course was going.

Session 9 of the 2nd WAN Feminism Introductory Course: “Globalization” Report by alary

The session of the day was titled "Globalization."

In relation to this topic, there was a question I had been thinking about for a while --

"Is it possible to eliminate gender inequality within the same race without sacrificing inequality between different races?"

Let me try to explain what I mean in more detail.

When I attended one of the lectures by Prof. Ueno in the past, I heard her say that "standardization within the same class is a mechanism that is achieved by expanding racial and class inequality."

In other words, equality between some classes can be achieved by sacrificing other inequalities such as race and class.

I personally have ever lived in the United States for about one year, and in light of this experience, the explanation did make sense to me.

During my time in the U.S., many white women hired immigrant women of different races as nannies (babysitters).

This allowed white women to continue working without having to quit their jobs or have their working hours restricted by childcare.

In other words, against the backdrop of the global North-South disparity, they employed immigrants at low wages to procure care work services from the market.

This was a mechanism to release white women from the responsibility of care work and to achieve some degree of gender equality between men and women of the same race (white).

…As a woman of color, I have complicated feelings when recalling this memory.

The equality they achieved was not due to an equal distribution of care responsibilities between men and women, but rather the result of women being freed from care responsibilities just like men.

And the care responsibilities that had originally been borne by white women were now borne by interracial women.

It seemed to me that "those who were racially/economically strong were simply imposing care labor onto others who were weaker than them."

From this thought, I decided not to use such services even if they were available.

However, when I actually started working, I began to think that it would be difficult to survive in the organization without using such services.

I was hired as a regular career-track employee, but I had to work a lot of overtime, and if I would move up to a managerial position, I was expected to contribute more than just overtime.

People who actually worked as managers seemed to be so busy that it would not be an exaggeration to say that they worked around the clock.

Because of this working environment, most managerial positions were naturally filled by men who had no care responsibilities.

There were some female managers, but most were single or childless, and even if they had children, they had their parents or parents-in-law look after them.

If they take on care responsibilities without access to the resources of their parents or parents-in-law, they would have to return home at least on time and possibly work shorter hours, even if the care work was equally distributed with their husbands.

However, unfortunately, I could not find a route for such personnel to be recognized as top-notch workforce and move up.

Those with care responsibilities (mostly women) seemed to be pushed into the so-called “Mommy Track” as second-rate workforce.

Many women quit before this point because of the burden of balancing work and childcare.

I thought that this is how the number of women who are able to become managers is decreasing (being reduced).

I began to think that the only way for women to compete with men on an equal footing is to outsource care labor services, as is practiced in the United States.

…When I raised this topic in a free discussion in the WAN course, Prof. Ueno asked the participants, "Do you support opening up the country to household workers? Would you use such a service if it existed?", to which a variety of opinions were expressed.

Those in favor of it said,

* For those from countries where there are no better jobs than migrant work, it is a chance to earn a level of income that they cannot get in their own country, even if the work is low-paid for those from the host country.

* I hope that people will be able to work in other countries of their choice if they wish to, regardless of occupational category.

The opinions of those opposed to the proposal included the following,

* Is there any point in equality built on inequality? Is that the kind of feminism we were aiming for?

* Is it possible to provide sufficient care to each individual by relying on others for care work?

In addition, some opinions were expressed such as:

* Before outsourcing care work, there are things that should be done, such as changing the mindset of men and properly valuing care work.

* The current government considers the technical intern trainees and those who have lost their status of residence to be disposable, they have no intention to take care of them in a long term, and the treatment is inhumane, so it should not happen while the current government is in power.

Based on these discussions, I would like to respond to Prof. Ueno's question.

My thoughts at this point are as follows.

Opening up the country to household workers is not ideal, but it is unavoidable as an emergency measure during the transitional period.

Of course, this is only possible if the human rights of foreign workers are guaranteed and the minimum wage is set at the same level as for Japanese workers.

It is important to change the mindset of men.

I also know that there is an option (the Swedish model) of changing the mindset of men, making care responsibilities equal between men and women, and then increasing public funding for care.

However, it will not be easy to modify a welfare regime that has once taken root in society.

While waiting for this to happen, women are dropping out one by one, and as a result, it is only men who become managers and make decisions.

This has probably been repeated over and over again.

Dual-earners now account for more than half of the population in society as a whole, and the number of couples in full-time employment has also increased.

Even if housework were divided 50:50 between husband and wife, there would still be limits.

We believe that there is a growing need for an environment in which housework services are readily available with a fee being paid.

Some may argue that it would be better to use housework services provided by Japanese people instead of foreign household workers.

(Putting aside for the moment the criticism that this is just taking advantage of the class disparity between women)

Housework services provided by Japanese people do exist, but they are not widespread enough to be considered common, and the fees may be too high for casual use.

However, I have heard that some companies are offering subsidies for babysitters recently as part of their "women's empowerment" measures.

If such initiatives become widespread, it may be easier to use housework services without relying on foreign household workers.

After the lecture, Prof. Ueno again asked the following questions.

As an electorate, I would like everybody to think about it.

(1) Do you support opening up the country to household workers?

(2) If you had a choice, would you be a user?

(3) Do you think you can be on the user side (do you have the purchasing power to do so)?

(4) In the first place, will foreign workers come to Japan with a weak yen in the future?

P.S.

At the end of the course, Prof. Ueno said, "It's strange that this has become a battle between women. If you trace it back to the roots, it's men who are at fault for not doing anything." I completely agree.

Another participant also commented, “Women are not appreciated (because it has become too commonplace) even though they cut back on their careers and private lives to take on unpaid labor. But when a man behaves in the same way, he is praised as an "ikumen" (a father who is good at raising children), while wives are asked to "groom" their husbands by expressing gratitude to them and flattering them.

Sometimes, when someone else takes over the role (or is paid for doing so), only women are plagued by an immense sense of guilt and express gratitude to the person... while men never feel that way. This imbalance is ridiculous in the first place." I agree with this too.

Translated by Maria KADONO

The original Japanese article: https://wan.or.jp/article/show/11220

2024.11.14 Thu

慰安婦

慰安婦 貧困・福祉

貧困・福祉 DV・性暴力・ハラスメント

DV・性暴力・ハラスメント 非婚・結婚・離婚

非婚・結婚・離婚 セクシュアリティ

セクシュアリティ くらし・生活

くらし・生活 身体・健康

身体・健康 リプロ・ヘルス

リプロ・ヘルス 脱原発

脱原発 女性政策

女性政策 憲法・平和

憲法・平和 高齢社会

高齢社会 子育て・教育

子育て・教育 性表現

性表現 LGBT

LGBT 最終講義

最終講義 博士論文

博士論文 研究助成・公募

研究助成・公募 アート情報

アート情報 女性運動・グループ

女性運動・グループ フェミニストカウンセリング

フェミニストカウンセリング 弁護士

弁護士 女性センター

女性センター セレクトニュース

セレクトニュース マスコミが騒がないニュース

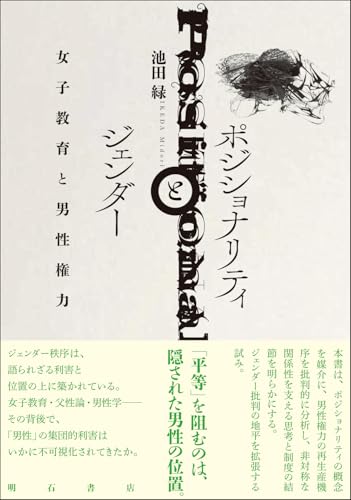

マスコミが騒がないニュース 女の本屋

女の本屋 ブックトーク

ブックトーク シネマラウンジ

シネマラウンジ ミニコミ図書館

ミニコミ図書館 エッセイ

エッセイ WAN基金

WAN基金 お助け情報

お助け情報 WANマーケット

WANマーケット 女と政治をつなぐ

女と政治をつなぐ Worldwide WAN

Worldwide WAN わいわいWAN

わいわいWAN 女性学講座

女性学講座 上野研究室

上野研究室 原発ゼロの道

原発ゼロの道 動画

動画

![[広告]広告募集中](https://wan.or.jp/assets/front/img/side_ads-call.png)